Good Artists Borrow, Great Artists Steal…But Do They Sleep Well At Night?

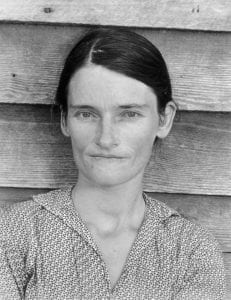

Walker Evans photo of Allie Mae Burroughs, 1936, for his book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, 1941, that Sherrie Levine photographed in 1981

This article was published in the January 2016 issue of Nashville Arts Magazine

by Rachael McCampbell

They say that imitation is the greatest form of flattery. But is it?

Media sources encourage us to follow the latest trends. Every season, we are told what the new “in” color will be; and it’s an accepted fact that within days of a couture fashion show, knock-offs of the top designers’ wares will be on the streets at a fraction of the price. But does this hurt the top designers? Actually, it’s been said it may even help them. The spread of a new style creates a trend, a fashion cycle, that might not have happened had it not been for the spreading of that idea through knock-offs.

In the fields of music and art, however, trends don’t come and go in the same way as the fashion world. A song can be financially impactful for decades as can a painted image. Illegal sampling of songs has become a tremendous issue for record labels and their artists; and in the visual arts, famous artists and their estates are constantly issuing cease-and-desist letters to people using their images on products that are not licensed.

Most artists are under the impression that once someone creates a piece of art, it’s automatically copyright protected—and since 1989 it is to some extent. But if someone copies your work, an artist doesn’t have much of a case unless the work has been properly registered with the U.S. Copyright Office. But what about copyrighting a style? What if an artist, for example, has spent a lifetime creating a distinctive style, and gets blatantly imitated by another artist? Can the artist sue the imitator for stealing their imagery and/or style?

I asked Nashville copyright lawyer Mark Patterson about this.

“Copyright protection exists from the moment the artist embodies the artistic work in a tangible form, which can include digital media,” Patterson says. “Copyright registration is optional for the protection to exist, but is required before a lawsuit can be filed against an infringer. Also, if an infringement commences before registration is obtained, some of the legal remedies available to the copyright owner [aka the artist] may be lost. To establish that an artistic work has been “copied” for purposes of copyright infringement, there must be: (a) proof that the alleged infringer had access to the artist’s work; and (b) substantial similarity between the artist’s work and the alleged infringing work. Merely changing an “element” in the work will not by itself be a defense if the overall work is substantially similar. On the other hand, mimicking an artist’s style is not copyright infringement if the works themselves are not copied.”

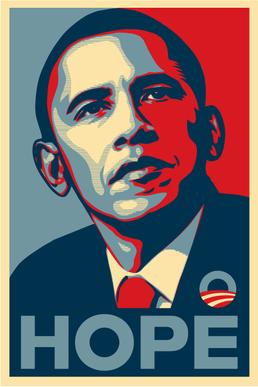

Hope poster/button by Shepard Fairey of Barack Obama based on a 2006 AP photo of George Clooney and Barack Obama

But in the fine-art world, the boundaries between art that has been changed enough and blatantly copied are blurred, to say the least. The courts’ determinations on copyright cases are often grey, and seem subjective and inconsistent. Shepard Fairey, for example, famously took an Associated Press photographer’s image of then-presidential candidate Barack Obama, altered it, and put the word “HOPE” below it. He sold posters, T-shirts, and buttons, which resulted in it becoming the most iconic image of the 2008 presidential campaign. The mixed-media stencil portrait was even sold to the Smithsonian for its National Portrait Gallery. However, it was determined that Fairey falsified evidence of his original source photo, saying that he had transformed the image enough to constitute “fair use” under copyright law, when in fact he has used a different photo as a resource by the same AP photographer. In the end, Fairey had to share future rights to the “Hope” image with the AP, provide the news agency an undisclosed amount of money, pay $25,000 in fines, and complete 300 hours of community service for falsifying and destroying evidence.

Yet, on the flip side, is the artist Elaine Sturtevant, who made a fine art career of copying famous paintings by Warhol, Jasper Johns, and others, not as a forger, but as a conceptual artist signing her name on the back. She was interested in the idea of authenticity, originality, icons, artist celebrity, and the art market’s ever-changing styles. The curator of a major exhibition of Sturtevant’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Peter Eleey, said, “In some ways, style is her medium.” Ironically, Sturtevant’s reworking of Roy Lichtenstein’s print of Crying Girl sold at auction in 2011 for $632,100 more than Lichtenstein’s original print version only four years earlier.

Then again, there’s Jeff Koons’ famous case where he used a postcard of a photo of a man and woman holding puppies and created a 3D sculpture of that image with clear changes, String of Puppies, and was sued. The court deemed that Koons had not altered the image enough under the “fair use” protection. He didn’t even make an exact copy of a photograph, he made a sculpture basedon a photograph and lost.

Sherrie Levine, who created a series called After Walker Evans, where she photographed Walker Evans’ iconic photographs from his book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, thought she was protected since the photographs were part of the public domain, but Evans’ estate sued and won gaining the rights to Levine’s series. To make things even more complicated, the conceptual artist Michael Mandiberg came along and created a digital appropriation piece of Sherrie Levine’s photos of photos with the website, www.aftersherrielevine.com, where one can download and print out copies of Sherrie Levine’s copies of Walker Evans photographs, with a certificate of authenticity for each image. At this point, who owns the copyright to any of it?

Back to the artist who knowingly imitates another artist’s style, gives that artist no credit, and goes on to license the imagery to be printed on napkins and cell-phone covers. There’s the saying, often attributed to Picasso, “Good artists borrow, great artists steal.” Yes, but do they sleep well at night? If you are an artist who borrows or appropriates from others as a part of your statement, then be aware that the laws are ambiguous and the courts could easily side for or against you. In my opinion, to avoid copyright infringement issues, work on creating a unique style and imagery that you alone generate. Isn’t that one of the biggest perks about being an artist anyway—that you get to express your original thoughts and feelings?

For more information on copyright laws and how to register your work, visit www.copyright.gov.